Success Story

Capacity Strengthening 2.0: Moving from the Aspirational to the Operational

December 12, 2023

Jeff Barnes, NPI EXPAND Project Director

Note: The views expressed in this piece are only those of the author and do not present the views of NPI EXPAND, Palladium, or USAID.

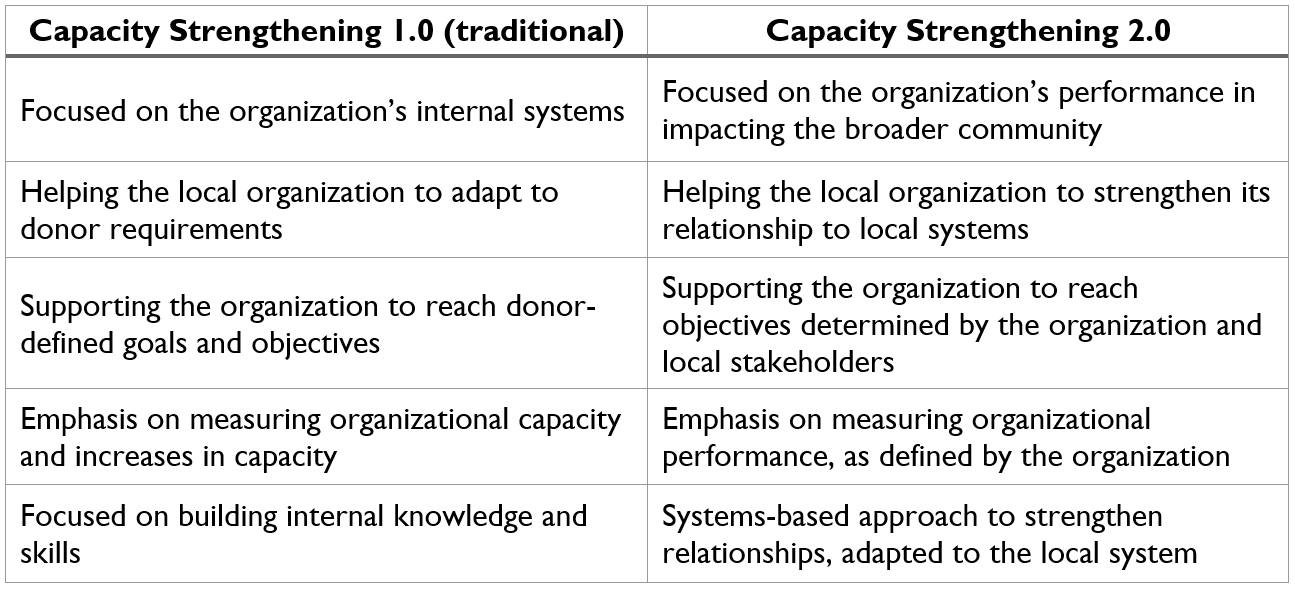

As one of USAID’s largest global projects focused on localization, NPI EXPAND has endeavored to adopt the recommended approaches of Capacity Strengthening 2.0. and adhere to the principles of USAID’s Local Capacity Strengthening Policy. As we enter our fifth year, when I review our capacity strengthening (CS) activities to date, it seems that we have only been marginally successful in moving away from Capacity Strengthening 1.0. For those who may not be familiar with these terms, here are some of the key differences:

In spite of our intentions to move from traditional approaches to Capacity Strengthening 2.0, we haven’t found it easy. Here are some of the reasons why:

1. Reliance on traditional CS approaches to focus on internal management of the organization

We strongly agree with the critique of the traditional approach of CS that too much time is spent focused on internal systems of the organization (financial management, HR systems, strategic planning, etc.), too much time getting the grantees to understand USAID systems, and not enough on interventions that help improve their performance. In spite of our desire to move away from this, the vast majority of our CS activities were still focused on internal organizational systems capacity. Why?

- Pressure to manage risks: We should not forget that most USAID-supported capacity strengthening occurs in the context of formal agreements which have principal-agent relationships built into them. As the prime for NPI EXPAND, Palladium is answerable to USAID. As the recipient of subawards from Palladium, our grantees are answerable to Palladium. In any such relationship, the first rule is to comply with the terms of the agreement. Failure to do so can result in cancellation of the agreement, failed audits, loss of funding, loss of employment, etc. In the light of such risks, it is understandable that project staff want to ensure that there are good systems in place to manage funds, ensure compliance and adhere to all the conditions that flow down from the prime to the subawardees. Having good organizational systems is also an advantage for an organization to attract new funding and to perform better, but the truth is that these investments have more to do with risk management than strengthening the capacity of the organization to implement better programs. The connection between contract compliance and financial management training and risk reduction is strong. The connection between that training and better health outcomes is tenuous at best.

- Organizations themselves prioritize investment in the traditional approaches to capacity strengthening: NPI EXPAND has been very careful to ensure that our local partners conduct their own self assessments and make their own decisions about what are their priority areas for capacity strengthening. Frequently, the priorities they identify are USAID compliance, HR management, knowledge management, governance, strategic planning, and resource mobilization. Rarely do they ask for help in improving their technical capacity. There are a few possible reasons they would also prioritize traditional approaches. First, the framework for self-assessment of needs is organized around the organizational capacity assessment tool which mainly focuses on internal management systems. Secondly, similar to prime organizations, local organizations are also concerned with risk management and want better systems to do so. Third, general notions of what constitutes “capacity development” revolve more around internal organizational systems than with the Capacity Strengthening 2.0 approaches of relationship building, social capital, and systems strengthening. While local organizations recognize the objective of strengthening their relationship with local health systems and other decision makers are important to their success, it is not always clear how to improve in those relationships through an intentional “capacity strengthening” activity. Where such capacities do get strengthened, it usually happens through program implementation and working collaboratively with other actors in the health system, not through a formal “capacity strengthening” activity.

2. Finding the overlap between the organizations goals and desired results and USAID’s

Capacity Strengthening 2.0 emphasizes the importance of helping the organization to achieve their goals, not the donor’s goals. While it is certainly desirable that an organization be clear about its mission and goals, it ignores the reality that USAID implementing partners face in having to adhere to activity areas that align with our funding streams. NPI EXPAND worked with different funding sources including population and reproductive health, maternal and child health, COVID-19, education, economic growth, nutrition, and others. Each funding source comes with a different client, a different set of standard indicators, and different expectations of what constitutes successful performance. USAID Missions did not give NPI EXPAND a mandate to simply select local organizations and find ways to support their organizational goals and mission. We were always given a specific scope of work in a defined area of development with specific objectives and illustrative activities. Our task was then to go out and find local organizations whose organizational capacity and goals aligned with USAID goals and desired results. When we do this through funding solicitations, it is not always easy to tell which organizations have truly embraced USAID’s goals as their own and which ones have simply adapted their organizational goals to the available sources of funding. Even when an organization clearly shows past and current commitment to similar goals, there are many instances in which we had to reconcile what the local organization wanted to do and what USAID asked us to do.

It would be ideal to support local organizations with unrestricted funding to support unsolicited proposals designed around objectives and activities conceived entirely by local stakeholders. Unfortunately, that is not the world we live in. The U.S. Congress requires different restrictions and earmarks on foreign aid and USAID has necessarily built its structures and systems around these requirements. Getting back to the principal-agent relationship, the system is set up around the notion that the principal (USAID) is “buying” specific results that the agent (local implementing partner) can deliver. The challenge we face is trying to find those areas where USAID’s goals and local goals overlap and implement agreements in a way that gives local stakeholders as much decision-making power as possible. It is important to be clear with ourselves and our grantees that we are looking for areas of common interest, not just supporting local goals.

3. Difficulties of measuring organizational performance

Another important feature of Capacity Strengthening 2.0 is to focus on capacity strengthening that improves the performance of the organization in terms of helping them to achieve their objectives and improve the contributions they are making to the health system in which they operate. It is critical to remind ourselves that we are strengthening organizations to ensure that they make a greater contribution to the development of the countries in which they operate.

The problem is that it is not always easy to define what improved performance should be and even what can be accurately measured within the timeframe of a typical USAID project or subaward. National governments may have detailed strategic plans and specific performance targets in each sector, but most local non-profit organizations do not. Mostly, they have very broad goals and are only able to set performance targets when they are funded to do so. So then there is a risk of confusing the organizational goals with the expected results of the program they are currently implementing. Then there is the other challenge of choosing performance indicators which the organizations have a reasonable chance of achieving. Any systems-level target that can be set such as increases in use, access, or quality involves many factors that are beyond the control of the local organization. Sometimes very high performing organizations that have implemented programs in line with best practices fail to reach targets because economic factors or social barriers were too difficult to overcome. Does that mean that the problem is with the organization’s capacity? I think not.

The more likely explanation for such “failures” is that the local organization just needs more time and resources to begin to move the needle on these important but challenging indicators. The average period of performance of NPI EXPAND’s awards was between 12 and 15 months. Allowing for the usual project processes of planning, staffing and procurement, this is hardly enough time to have measurable, systemic impact.

The way forward

Interestingly, when I look at some of our programs, I think we have been more successful in realizing the ideas behind Capacity Strengthening 2.0 in our program activities, and not in what we call our capacity strengthening activities. The idea of helping local organizations to improve their relationships and fit into the local system has been an operational principle in nearly all of our activities. In Narok County, Kenya, our grantees have developed strong relationships with the county government to jointly plan and implement provider training and quality improvement activities. In Ethiopia, our grantees have filled a critical gap in the national approach to social accountability by helping to create Community Councils and empower marginalized groups to take an active role in governance of public health facilities.

This is itself instructive. We have to recognize that the most important capacity strengthening activities are simply giving local partners the opportunity to build up their experience in program implementation and develop the relationships and learn the operational lessons that can only come from experience. We have to broaden our notion of capacity strengthening and blur the distinction between implementation and capacity strengthening activities. Capacity strengthening is not the icing on the cake—it is (or should be) baked into the cake itself.

What local organizations need most to build their capacity is more experience leading the design and implementation of programs with sufficient resources and continuity in funding that helps them overcome the boom-and-bust cycle of project start up and closures.

Overall, the ideas behind Capacity Strengthening 2.0 and the ideas behind USAID’s new Local Capacity Strengthening Policy are important aspirational guidance. But it is important to adapt that aspirational vision to the operational reality implementing partners face.